The Rating of Poets • The Rating of Poems

Horace Smith. Biography

SMITH, HORATIO, always known as Horace (1779–1849), poet and author, born in 1779, was second son of Robert Smith (d. 1832), and younger brother of James Smith (1775–1839) [q. v.] A sister was the mother of Maria Abdy [q. v.] The father, Robert Smith, was born at Bridgwater, Somerset, where his father, Samuel, was a custom-house officer, on 22 Nov. 1747; he entered a solicitor's office in London in 1765, and married in 1773 Mary, daughter of James Bogle French, a wealthy London merchant. She died, aged 55, at her husband's residence in Basinghall Street, on 3 Nov. 1804. Robert Smith was for many years solicitor to the board of ordnance, a post he resigned in 1812, and he was elected F.R.S. on 24 Nov. 1796, and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. He was eighty-five when he died, on 27 Sept. 1832, at St. Anne's Hill, Wandsworth (Gent. Mag. 1832, ii. 573; cf. ib. 1804, ii. 1078 and 1050, containing a poem by H[orace] S[mith] upon his mother's death).

Like his brother, Horace was educated at a school at Chigwell, kept by the Rev. Mr. Burford, but, unlike James, was placed in a merchant's counting-house. Less attentive to business than to the drama and the amusements of the town, he produced a poem lamenting the decay of public taste as evinced in the neglect of the plays of Richard Cumberland, who, highly flattered, hunted him out of his counting-house and introduced him to literary society. He published two novels, ‘The Runaway’ in 1800, and ‘Trevanion, or Matrimonial Ventures,’ in 1802. A third, ‘Horatio, or Memoirs of the Davenport Family,’ followed in 1807. Meanwhile, in 1802, Smith joined with Cumberland, his brother James, Sir James Bland Burges, and others in writing for ‘The Pic Nic,’ a magazine which was edited by the notorious William Combe [q. v.], but had only a brief existence. At Cumberland's request, Horace and James wrote several prefaces for plays in ‘Bell's British Theatre,’ edited by him; and their acquaintance with Thomas Hill led both, but especially James, to contribute for four years to his ‘Monthly Mirror.’ They acquired a character as wits, and as gay, though not dissipated, young men about town, but were little known to the public, when they suddenly found themselves raised to the pinnacle of contemporary reputation by the utterly unforeseen success of their ‘Rejected Addresses’ (1812). These were parodies of the most popular poets of the day in the guise of imaginary addresses from their pens which purported to have been prepared in competition for a prize that had been offered by the managers on occasion of the reopening of Drury Lane Theatre after its destruction by fire (10 Oct. 1812). Horace Smith himself had been a serious competitor, and the commission had been entrusted to one of the poets parodied, Byron. The idea had been suggested to the Smiths by the secretary to the theatre, Mr. Ward, Sheridan's brother-in-law, who, having seen the addresses submitted bona fide, had been struck by their prevailing silliness, no less than sixty-nine competitors having invoked the aid of the Phœnix. The brothers had great difficulty in finding a publisher, until at last John Miller, of Bow Street, agreed to print at his own expense, and give them half the profits, ‘if any.’ The volume appeared on the day of the opening of the theatre, with the title ‘Rejected Addresses, or the New Theatrum Poetarum’ (18th edit. 1833, with new preface by Horace Smith). Success was instantaneous, and in truth there has been nothing better of the kind in the language, excepting only Hogg's inimitable parody of Wordsworth, ‘The Flying Tailor.’ In the ‘Rejected Addresses’ the best parodies were those of Cobbett and Crabbe, and were the work of James Smith, who also wrote the hardly less successful parodies of Wordsworth and Southey. Horace Smith's best are those of Byron and Scott, and the delectable nonsense of ‘A Loyal Effusion’ by William Thomas Fitzgerald [q. v.] Horace inserted his genuine rejected poem under the title of ‘An Address without a Phœnix.’ Neither brother did anything half so good again, though each has bequeathed a considerable amount of comic verse, never destitute of merit, but always courting comparison with the similar productions of Thomas Hood, and hopelessly distanced by them. Their only subsequent joint production, entitled ‘Horace in London, by the authors of Rejected Addresses,’ appeared in 1813.

After his apprenticeship in the counting-house was over, Horace Smith went on the stock exchange. He was probably a good man of business, for he throve so fast as to be able to retire in 1820, and was blamed for throwing away the prospect of a fortune. But when the panic of 1825 came, he congratulated himself on his good sense. Before retiring he had gained the friendship of poets and performed numberless generous actions. His good sense and conciliatory disposition are admirably shown in his letter to Sir Timothy Shelley on the temporary stoppage of Shelley's income. He was Shelley's guest at Marlow in 1817, and he was probably the first to communicate Keats's death to the poet in March 1821. Shelley wrote of him in his epistle to Maria Gisborne:

Wit and sense,

Virtue and human knowledge, all that might

Make this dull world a business of delight,

Are all combined in Horace Smith.

To Leigh Hunt he was equally friendly and equally serviceable, joining with Shelley in the vain effort to rescue him from his embarrassments. His endeavours, however, to follow in the footsteps of these poets were not always fortunate. Nevertheless, ‘Amarynthus the Nympholept,’ a pastoral drama in imitation of Fletcher (1821), is full of pleasant fancy. Not much can be said in favour of his other serious poems (first collected as ‘Poetical Works,’ London, 1846, 2 vols. 8vo), except the fine lines on occasion of the funeral of Campbell in Westminster Abbey, when, late in life, the deep feeling aroused by the recollection of a long friendship supplies the deficiencies of poetic art. There is, however, a class of poems in which Smith really excels, those halfway between the serious and the humorous. One of these, ‘An Address to a Mummy,’ has deservedly gained great popularity, and is an admirable example of the mutual interpenetration of wit and feeling.

On his retirement from business, Smith set out to join Shelley in Italy, but on hearing of his death stopped short at Paris and lived for three years at Versailles; on his return he settled at Brighton. He now added Cobden to the list of his friends, and became a warm advocate of free trade. He aided Campbell in the ‘New Monthly’ and John Scott in the ‘London Magazine.’ Some of his pieces were collected as ‘Gaieties and Gravities’ (London, 1825, 3 vols. 8vo). But about the same year he gave up periodical literature to resume his early pursuit of novel-writing. In 1826 he produced ‘Brambletye House, or Cavaliers and Roundheads,’ a romance in Scott's style, connected with a ruined mansion of the name still existing in Ashdown Forest, Sussex. It ranks among the best imitations of Scott, and has been frequently republished. ‘The Tor Hill’ and ‘Reuben Apsley,’ two good historical novels, followed in 1826 and 1827, and in 1828 he varied his style by imitating Lockhart and Croly in ‘Zillah, a Tale of the Holy City’ (London, 12mo). Both this work and ‘Tor Hill’ were translated into French by Defauconpret, the translator of Scott and of Mrs. Radcliffe. A severe attack on ‘Zillah’ in the ‘Quarterly’ gained him the friendship of Southey, after he had done penance for ‘some impertinences regarding Wordsworth.’ His later novels, rarely historical in subject, obtained little success; they include ‘The New Forest’ (1829), ‘Walter Colyton’ (1830), ‘Gale Middleton’ (1833), ‘The Involuntary Prophet’ (1835), ‘Jane Lomax’ (1838), ‘The Moneyed Man’ (1841), ‘Adam Brown’ (1843), and ‘Love and Mesmerism’ (1845). A posthumous fragment from his pen, professedly but not really autobiographic, appeared in vols. lxxxvi. and lxxxvii. of the ‘New Monthly Magazine.’ His other writings include ‘First Impressions,’ an unsuccessful comedy (1813); ‘Festivals, Games, and Amusements, Ancient and Modern’ (1831), a useful compilation; and ‘The Tin Trumpet,’ (1836), a medley of remarks, ethical, political, and philosophical. It was published under the name of Jefferson Saunders, but Smith's name appeared on it in 1869 when it was issued as No. 8 in Bradbury and Evans's ‘Handy Vol. Series.’ Keats, in a letter written in February 1818, mentions having seen in manuscript a satire by Smith entitled ‘Nehemiah Muggs, an Exposure of the Methodists,’ but it does not appear to have been published. He died at Tunbridge Wells, on 12 July 1849. He left three daughters, of whom the youngest, Laura (d. 1864) married John Round of West Bergholt, Essex.

All contemporary testimony respecting Horace Smith is unanimous as regards the beauty of his character, which was associated not only with wit, but with strong commonsense and justness of perception. His is a remarkable instance of a reputation rescued from undue neglect by the perhaps excessive applause bestowed upon a single lucky hit. Thackeray wrote warmly of Smith's truth and loyalty as a friend, and, after his death, he frequently visited his daughters at Brighton; after the youngest of them he named his Laura in ‘Pendennis.’

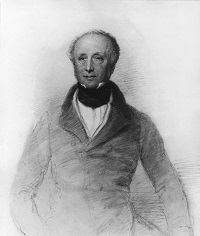

A portrait of Horatio and James Smith in early life by Harlow is in the possession of Mr. John Murray. A portrait of Horace by Masquerier and a miniature were the property of his eldest daughter.

Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900

Horace Smith's Poems:

8546 Views

English Poetry. E-mail eng-poetry.ru@yandex.ru